A Wilde Encounter with The Picture of Dorian Gray Adapter-Director Kip Williams

(Photo c/o The Press Room)

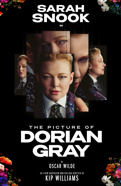

Last year, when The Picture of Dorian Gray, starring the actress Sarah Snook, premiered at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in London, the show’s Australian adapter-director Kip Williams made a habit of visiting, in the deep recesses of the building, the Oscar Wilde Room. The West End theater was reputedly Wilde's favorite. “At the end of every preview," Williams said, "I would go and make a little offering.”

On a recent Friday, Williams—wearing an artfully paint-splattered denim shirt and a baseball cap—visited the Morgan Library & Museum to once again connect with his (sort of) collaborator.

In one of the Morgan’s least ornate rooms, a banquet of Wildean treasures, including the entirety of the earliest surviving draft of The Picture of Dorian Gray, written in Wilde’s own hand, were on view. Philip Palmer, the curator and head of the manuscripts department, had the air of an upscale candy store owner showing off his treats. “The aura of these objects is absolutely incredible,” he said.

Williams drank in the sight of Wilde's first page, with its sensuous opening sentence: “The studio was filled with the rich odor of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden there came through the open door the heavy scent of the lilac, or the more delicate perfume”—here Wilde had inserted a caret and added the word pink—“of the pink flowering thorn.”

It’s a sentence, Williams said, that will likely swirl around his consciousness on his deathbed. That sentence—and the novel’s final one—remain intact in his stage version.

He approved of the adjectival addition. “It’s just a better rhythm for the end of the sentence.”

“It’s sort of like a musician fine-tuning the music,” said Palmer, bringing Williams’ attention to page 20, where Wilde had cut two highly erotically charged sentences expanding Basil’s description of Dorian sitting for his portrait. “The world becomes young to me when I hold his hand,” reads one excited, excised sentence, “as when I see him, the centuries yield all up their secrets!” Wilde replaces a brushing of the cheek with a chaste grazing of the hand.

Williams snapped a photo and texted it to Snook. “It’s interesting seeing the self-censoring,” he said. “It speaks to Basil’s anxiety at the very top of the story. That he’s afraid of the artwork revealing too much of himself. It’s at the core of the story itself.” (Another important Wildean artefact on display: one of the few surviving letters from Wilde to his lover "Bosie"—Lord Alfred Douglas. Douglas destroyed much of the rest.)

Eyeing Wilde’s intricate lettering, Williams observed, “He takes a lot of pride in his handwriting.” (An expert handwriting analyst once detected, in Wilde’s script, a tender heart and a craving for romance.) Though, on the last page of the manuscript, Wilde signs it with a surprisingly violent swipe of the fountain pen.

Williams was charmed by a lithograph featuring Wilde shilling Marie Fontaine’s Moth & Freckle Cure. “I didn’t quite realize that his celebrity at that point extended as far as product advertisement,” he said.

Growing up in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, Williams was just 15 when he co-founded a theater company, presented a Dadaist take on Macbeth and performed in a school production of The Importance of Being Earnest. “I was at an all boys’ school, so I played Cecily Cardew. I played it for psychological truth.” Something was ignited. “Wilde was all about sexuality and queerness and gender. So I’ve always encountered his work through those lenses. I immediately read The Picture of Dorian Gray as a teenager and just kept coming back to it obsessively throughout my life.”

A theater-maker who found early momentum—at 30, he became the youngest artistic director of Australia’s leading stage company, Sydney Theatre Company—Williams had long considered doing his own version of Earnest. But reading Dorian Gray “for the umpteenth time” instantly unlocked something about the story’s theatrical potential.

“He’s such an extraordinary dramatist,” he said of Wilde. “In the novel, it does feel like someone is speaking directly to you. Instinctively, for me, it felt like it was a text that would land in that very ancient form of theater, of having an actor come to an audience directly to tell a story.”

Williams transformed Wilde’s mellifluous prose into a high-tech thrill ride, with one actress playing 27 roles in dizzyingly complex interplay with multiple screens and cameras. It was, he said, “the most terrifying creative leap” of his career. The discovery of a line from one of Wilde’s letters affirmed his whole approach: “He describes the three different characters being different facets of his own identity. I felt like that was a sign from Wilde that I was on the right track. It was one of those rare lightning-bolt moments.” A cinematic adaptation is in the works.

Williams (who was, incidentally, speaking to a former Sydney theater journalist) also took a moment to reflect on the vitality of the Sydney theater scene he came up in. “I was very fortunate to be a young aspiring practitioner in a city where there was such a depth of inspiration to be found. Australia is an incredible crucible for theater-makers. We're used to traveling to see the best that the world has to offer. Then we bring all those influences back. It's melded with our own specific theater traditions—think of the incredible First Nations culture that we have in Australia. It creates a really unique breeding ground for experimentation and innovation and very bold works of theater.”

Before leaving the Morgan, Williams circled back to inspect Wilde's first page once more. “It’s pretty extraordinary,” he said. “I’ve been sitting with this story for so many years and it feels like having him in the room. Knowing the text so well, to see the little revisions he’s made—and to have such an intimate understanding of the rhythmic implication of changing a word, crossing out a sentence… It’s like getting to watch him make those decisions and connect that to the decisions I made over a century later.”

Even under the decidedly un-Victorian fluorescence of the room, there was something fittingly Gothic about it. “It feels like communing with the dead.”